Directed by Ishiro Honda. Written by Takeshi Kimura and Takeo Murata. Starring Kenji Sahara, Yumi Shirakawa, Akihiko Hirata.

Rodan is where Toho Studios’ science-fiction boom truly takes flight. The original 1954 Godzilla was an enormous success, but the rushed and less imaginative sequel, Godzilla Raids Again (1955), made money without leaving much of an impression on audiences or the Japanese film industry. Godzilla wouldn’t return to movie screens for seven years.

Then Rodan swooped in, an ambitious production photographed in Eastmancolor. The switch to color was significant: Rodan was not only the first giant monster film in color, it was only the second color film from Toho. (The first was the fantasy period piece The Legend of the White Serpent, a.k.a. Madame White Snake, released earlier that year and also featuring special effects by Eiji Tsuburaya.) Less than a tenth of the films made in Japan in 1956 were shot in color, making any color release a mark of prestige. Ishiro Honda, who brought dramatic intensity to Godzilla, returned as director, cementing his role as Toho’s head craftsman of science-fiction films.

Sora no daikaiju Radon (“The Giant Monster of the Sky, Rodan”) was a smash hit upon its domestic release. It was also a significant global success when the King Brothers released an English version to international markets. The move to color for Toho’s science-fiction films was a shrewd one as it made their product stand out from the lower-budget black-and-white Hollywood monster films of the period. A new market opened up, and Toho and Eiji Tsuburaya’s effects team entered one of the most productive periods of their careers.

Rodan originated from producer Tomoyuki Tanaka’s interest in exploring the popularity of supersonic jets (an interest that later produced the Ultra Q episode “The Disappearance of Flight 206”) and finding a way to apply that to a monster film. He hired writer Ken Kuronuma, author of several books on paranormal phenomena, to develop the story. Writers Takeshi Kimura and Takeo Murata then molded the story into the final script.

Rodan still shows the influence of the documentary approach of Hollywood science fiction, but not to the same extent as Godzilla. Ishiro Honda adapts his style with a more naturalistic warmth, emphasizing the workaday lives of the characters and taking in outdoor vistas.

The story begins at a coal mine near Mt. Aso on the southernmost of the Japanese islands, Kyushu. Two workers who recently had a violent feud vanish in the tunnels. One of them turns up dead, killed with a sharp instrument. When mine guards search the tunnels looking for the other missing miner, they die as well.

The real killers are Meganurons, the giant larvae of prehistoric dragonfly creatures. The Meganurons have burrowed up from the lower tunnels after their dormant eggs hatched. The scenes with these caterpillar-like creatures are legitimately effective as horror pitched on a human-scale, which makes for a good opening to a movie that will eventually broaden to a massive scope. Watching screaming miners get dragged beneath the water by an unseen attacker is unnerving, and the scene of the police trying to kill the creatures in claustrophobic tunnels has some of Honda’s best suspense direction. These sequences were likely inspired by the finale of Them! (1954), the classic “big bug” film of the ‘50s, where the military tries to wipe out a nest of giant ants in the Los Angeles storm drains.

After an earthquake causes part of Mt. Aso to collapse, Shigeru (Kenji Sahara, future Ultra Q lead), a miner who vanished during a Meganuron attack, is found wandering the crater in a catatonic state. While doctors try to get Shigeru to remember what he’s seen, mysterious flying objects moving at supersonic speeds start harassing the skies over Japan, China, and the Philippines. They even kill a couple picnicking on Mt. Aso with a sonic boom.

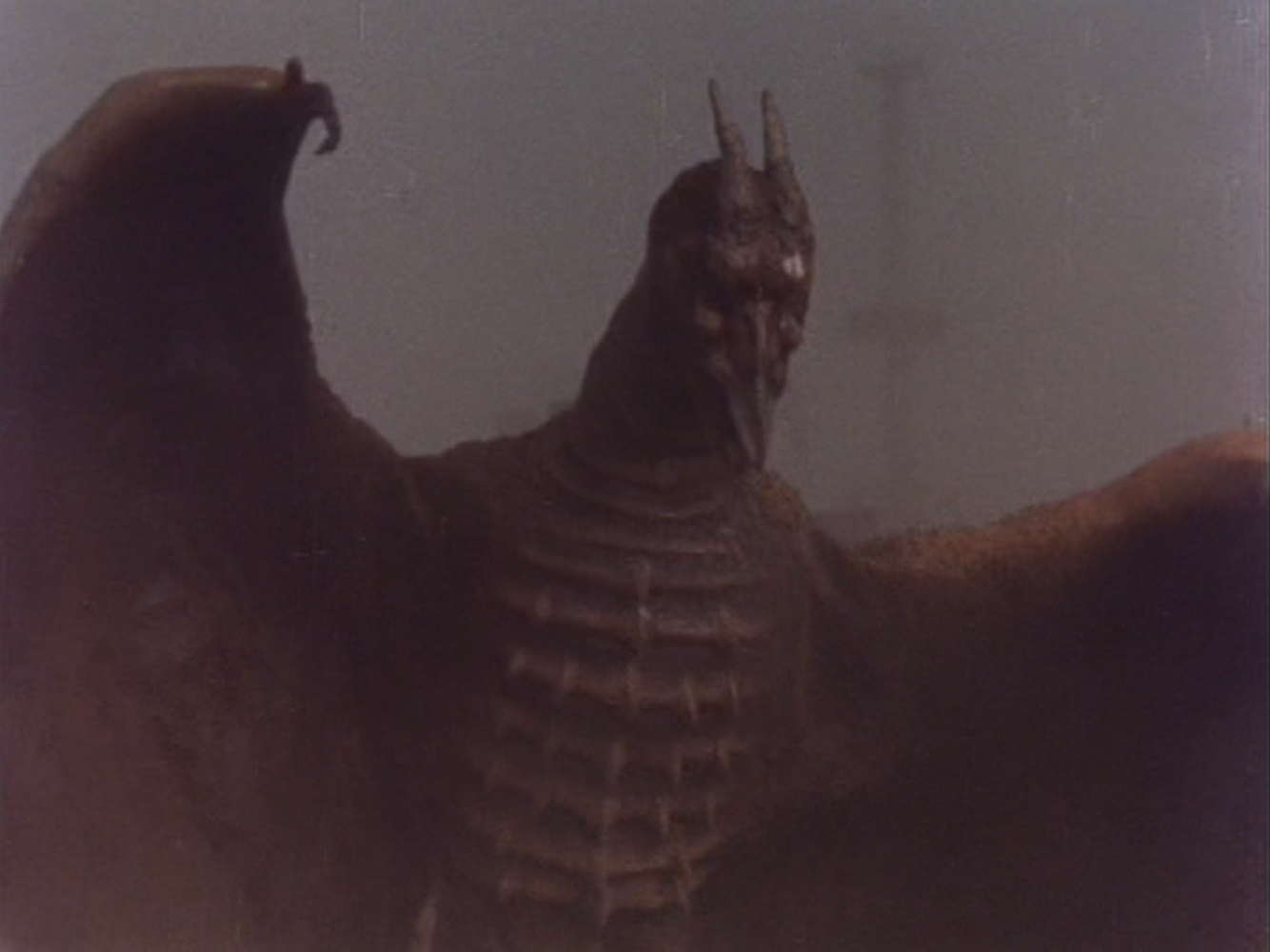

A visual shock causes Shigeru to recover and recall the trauma that paralyzed him. Deep in the caverns of the volcano, he saw a winged reptilian creature hatch from a giant egg and feast on the Meganurons. The flashback of the hatching of the title monster is grotesque with a touch of Lovecraftian nightmare. The score from Akira Ifukube is especially effective here, heavy and hallucinogenic.

Scientists, led by future Ultra Series supporting actor Akihiko Hirata (Dr. Iwamoto in Ultraman) determine that they’ve discovered a jumbo-sized version of Pteranodon with a 270-foot wingspan and the ability to fly at supersonic speeds. How a saurian creature can do this, as well as how it got so enormous, isn’t explained, although there’s a brief mention of hydrogen bomb testing. This doesn’t hurt the movie at all because it’s part of the weird magic of Japanese kaiju — they’re not so much monsters as primordial demigods. Of course Rodan can travel faster than the speed of sound!

At this point, Ishiro Honda’s dramatic storytelling moves to the background and Eiji Tsuburaya’s effects unit shows off what they’ve learned over the past few years. The Rodans — yes, there are two of them — come to center stage and the special effects work is a cornucopia of models, matte paintings, effects animation, and pyrotechnics.

First, the Japanese Self-Defense Force jets engage Rodan in a thrilling aerial duel scored to one of composer Akira Ifukube’s best marches. The dogfight ends in the destruction of the immense Saikai Bridge, a complex model built to 1/20 scale that the effects team destroyed in a single complicated take.

The Rodans then land in Kyushu’s largest city, Fukuoka, for the film’s centerpiece: an apocalyptic urban destruction that’s one of the peaks of kaiju cinema. JSDF tanks and missiles launch a blistering assault on the Rodans, but firepower is no match for the maelstrom from the monsters’ wings that levels the middle of the city.

The fast, kinetic mayhem in Kyushu is a stylistic change from the famous Tokyo rampage in Godzilla, which Tsuburaya orchestrated as slow-building doom. Here, Tsuburaya and his team fill the sky with smoke and debris, shred shingles off roofs, and hurl vehicles through the air to demolish buildings. The enormous amount of time, money, and effort required for the details put on screen is mind-boggling. The footage was so impressive that it ended up recycled in numerous later Toho films as well as the Ultra Series. (A good portion of the finale of “I Saw a Bird” comes from Rodan.)

The film concludes back at Mt. Aso, an enormous miniature built to ⅓ scale. This is the only spot where Rodan stumbles a bit. The rocket assault on the volcano crater where the two monsters are hiding goes on too long, with one explosion after the other. Impressive explosions, but the bombardment stretches on for two minutes more than it should. But the last moments of the Rodans among the lava flows are touching. The film takes a slow breath as Ifukube’s score turns elegiac. For both Honda and Tsuburaya, monsters could be something more than monsters.

Rodan had a strong later career as a co-star in Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964), Invasion of Astro-Monster (1964), Destroy All Monsters (1969), and continued into the Heisei era with Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II (1993). In the Millennium era, Rodan wrecked parts of New York in Godzilla: Final Wars. The monster then flew to Hollywood to become a scene-stealer in Legendary’s Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019). Meganuron made a comeback as well, appearing in Godzilla vs. Megaguirus (2000).

Even today, Rodan stands out. Its scale and the energy of its destruction were a leap forward in the scope and creativity of Japanese science-fiction filmmaking. The movie doesn’t have Godzilla’s bleakness or powerful message, but it’s still a masterful kaiju epic tinged with horror. Honda cited the movie as one of his personal favorites thanks to the passion of everyone who worked on it. That passion still comes through.

Rating: Classic