My plan for these show introductions is to keep them short(ish). This is one of the exceptions. As the launch site for a mammoth franchise, Ultra Q demands a deeper look into its background and an introduction to several of the key figures in the history of the franchise. And I’m still going to have to skim over a lot.

My succinct description of Ultra Q for newcomers is “The Twilight Zone meets Godzilla meets The X-Files.” That still isn’t quite right — once you see an episode like “Kanegon’s Cocoon,” the wheels of categorization fly right off — but it positions Ultra Q in a succession of genre archetypes that makes sense.

The comparison to The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits is the easiest to make, and many have made it; both US shows were acknowledged influences on Ultra Q’s production. But the show rapidly took on its own life under the guidance of its creative team and the style of its visual effects. The show has Twilight Zone’s variety, but it’s also more comic and quirky. The Twilight Zone struggled with comedy material, but Ultra Q made humor one of its defining aspects. It has monsters like The Outer Limits, but of a specifically Japanese variety, and that doesn’t just mean that many of them are giant monsters. These creatures came from the style and imagination of the man behind the Ultra phenomenon, special effects creator and all around wizard of the fantastic, Eiji Tsuburaya (1901–1970).

Development

Telling the full story of Ultra Q would require telling the life story of Eiji Tsuburaya. I’ll give an abbreviated version here; you can find out more at the references I’ll link to below.

Tsuburaya was the maestro of Japanese special effects and one of the co-creators of Godzilla. In my mind, Eiji Tsubaraya and Ray Harryhausen divide the world of special effects between them — the two VFX geniuses to whom every special effects artist today owes their eternal gratitude. Where Harryhausen mastered stop-motion animation, Tsuburaya pioneered “suitmation” and modelwork visual effects. His work for the Godzilla films and many other Toho SF and monster (kaiju) movies — most directed by Ishiro Honda — was done at a scale never before seen in movies from any part of the world. Tsuburaya brought not only scope and technical precision to his effects scenes, but also colorful imagination and a painter’s sense of beauty. Watch Godzilla’s rampage through Tokyo in the original 1954 Godzilla and you’ll see a master artist at work. Other Tsuburaya masterpieces include the effects for The Mysterians (1957), Battle in Outer Space (1959), Gorath (1961), and Atragon (1963).

By the mid-1960s, Tsuburaya was one of the most powerful people at Toho Studios, heading up their special effects department. In 1963, as the kaiju movie craze was rising toward its peak, Tsuburaya founded his own company, Tsuburaya Productions, to create special effects movies and television programs. He worked with science-fiction writer Testuo Kinjo, a key figure for the early Ultra shows, on a concept called Woo about an alien who comes to Earth and eventually adopts it as his second home. Woo never got made, but it laid the groundwork for much of the future of Tsuburaya Productions.

In 1964, Tokyo Broadcasting Service (TBS) asked Tsuburaya Pro to create a science-fiction series for one of their major sponsors. The network rejected the pitch for Woo, so Eiji Tsuburaya and Tetsuo Kinjo turned to a new idea. Kinjo proposed a show called Unbalance that drew inspiration from The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, both of which had recently aired on Japanese TV, as well as the British Quatermass television serials and their movie adaptations from Hammer Films. Kinjo’s premise was that Earth is undergoing a fundamental change due to human tampering, resulting in the titular unbalance and the emergence of strange creatures and bizarre phenomena. Unbalance evolved further when TBS made several requests, such as putting more emphasis on the giant monsters that Japanese audiences in the mid-1960s could not get enough of.

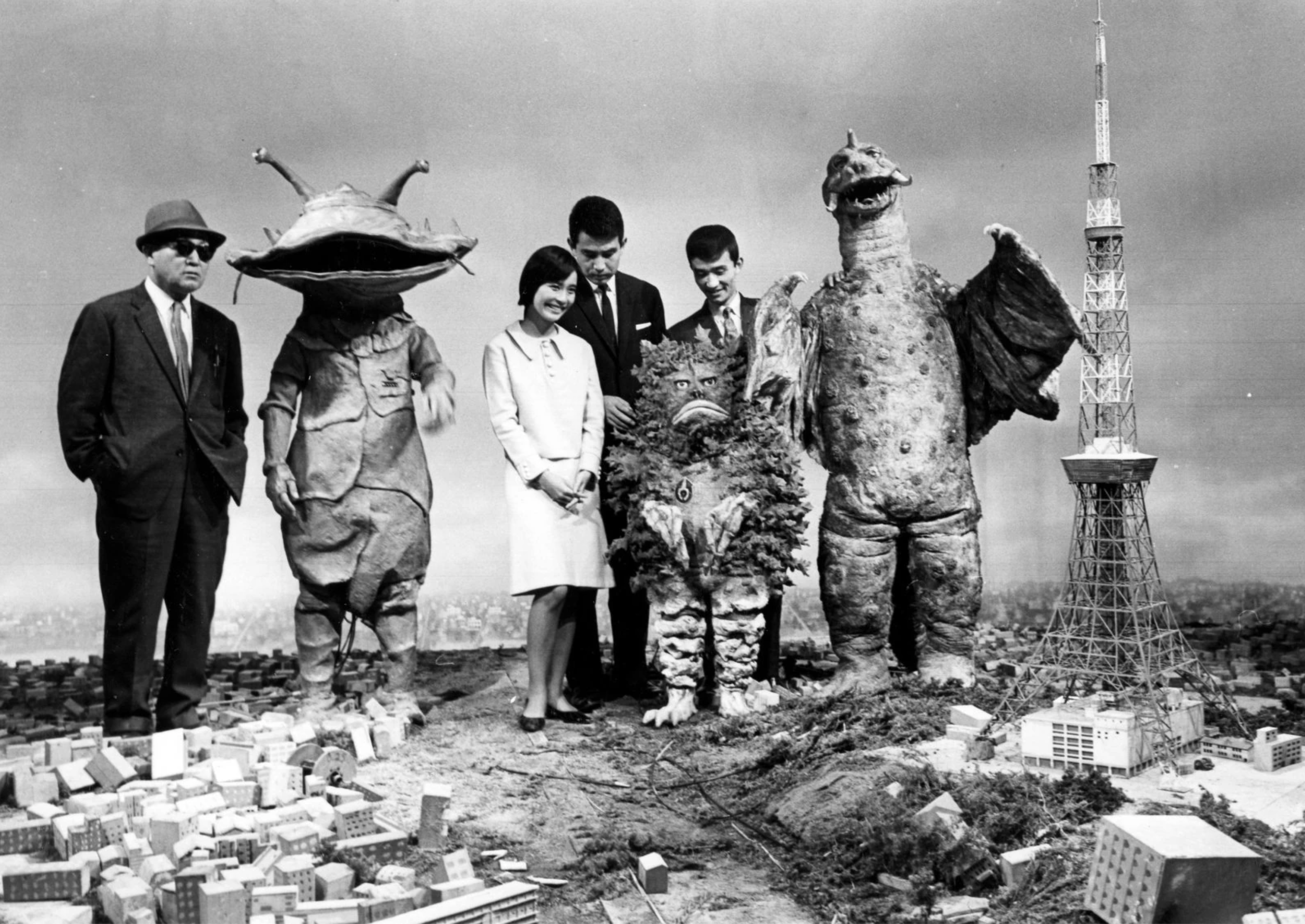

TBS greenlit the show, which would have its title changed to Ultra Q based on a popular catch-phrase from the 1964 Tokyo Summer Olympics. (“Ultra-C” was the name that gymnast Yukio Endo gave to his impressive parallel-bar maneuver.) The creative team started to form. Testsuo Kinjo served as the head writer and production manager. Avant-garde designer and sculptor Tohl Norita created many of the show’s monsters, which Ryosaku Takayama and the crew of his workshop then brought to life. Tsuburaya’s regular collaborator Sadamasa Arikawa joined the VFX team. Tsuburaya brought on his son Hajime as one of the rotating series of directors. Composer Kunio Miyauchi wrote episode scores and created the main title music, a jazzy and sinister number that feels like James Bond in a dark dimension.

The Cast

Ultra Q isn’t a straightforward anthology show like its American inspirations. It has a regular cast of three characters who investigate the bizarre phenomenon of the week, or sometimes serves as bystanders and observers of the bizarre phenomenon. These investigators and their recurring scientist pal sometimes feel like The X-Files and sometimes like Scooby-Doo, so add those onto the pile of comparisons for this unique show. Nerdist flat-out called Ultra Q “The Japanese X-Files,” but if I made you think of Scooby-Doo as well, you’re welcome. Considering some of the swerves of the comedic episodes, it’s not as far off as it sounds.

The three protagonists set a template many future Ultra shows would use for the defense teams: the stolid hero, the funny guy, the feisty girl.

For the lead character Jun Manjome, a Cessna pilot with Hoshikawa Air Service and a budding SF writer, TsuPro cast Kenji Sahara, an anchor of kaiju films. Sahara has racked up more Toho monster and SF movie credits than any actor, starting with a small role as a sailor in Godzilla and graduating to leading man status soon after in Rodan. He went on to appear in most of Ishiro Honda’s other science fiction films. (I’m most fond of his villainous turn as the sleazy head of Happy Enterprises in Mothra vs. Godzilla.) To back up the experienced Sahara were two younger actors, Yasuhiko Saijo as Ippei Togawa, Jun’s junior pilot partner, and Hiroko Sakurai (only 19 when she was cast) as Yuriko “Yuri” Edogawa, a spunky photographer on the monster-beat for Tokyo’s Daily News.

Along with the main trio are several semi-regulars. Professor Ichinotani (Ureo Egawa) serves as the wise polymath who has whatever obscure knowledge an episode might need. Ichinotani was originally intended as a bookend narrator, the Rod Serling of the show, but this idea was dropped early; popular radio performer Koji Ishizaka took on the role of a disembodied narrator. For the role of Seki, Yuriko’s boss at the Daily News, TsuPro cast another familiar face from Ishiro Honda’s SF movies, Yoshifumi Tajima. (His best role is also in Mothra vs. Godzilla, where he plays Kenji Sahara’s even sleazier underling.)

Production & Debut

With the cast and crew in place and money from TBS and sponsor Takeda Pharmaceuticals, production on Ultra Q got underway in September 1964 when Testsuo’s first script, “Mammoth Flower,” went before cameras on the stages at the Tokyo Art Center. Production was occasionally rocky, with regular budget problems that required TsuPro borrow costumes, props, and sets from Toho Studios. However, Eiji Tsuburaya’s experience with special effects and his belief in the show kept everything together.

Ultra Q was in production for 15 months and wrapped in December 1965 with 28 episodes ready to air. TBS ramped up promotion with a 15-minute promotional spot, The Mystery of Ultra Q: The World of Monsters. The show debuted on January 2, 1966 with the episode “Defeat Gomess!” Episodes weren’t aired in production order: for example, the last episode produced was the tenth to air, and the first episode produced was aired fourth. But the show was episodic, with none of the two-parters of later Ultra programs, nor did it have specific opening and closing episodes, something else that would become a tradition starting with Ultraman.

The network’s faith in the show wavered during production, but this changed as the premiere day got nearer. Even before the first episode aired, TBS sensed they had a hit on their hands. They were right. Ultra Q was a sensation from the start, pulling in an average 30% share and peaking at 36.8% with the episodes “Garadama” and “Tokyo Ice Age.” These are astonishing figures for the time and impossible today. Japan was Ultra crazy. TBS was so thrilled that even before Ultra Q started airing, they requested TsuPro get a follow up ready — the show that would become Ultraman and ensure an ongoing franchise that’s still hurtling along today.

The Greatness of Ultra Q

It’s difficult to express in a small space what a powerhouse Ultra Q was in Japanese TV and popular culture. From the Ultra DX Blog:

While Ultra Q doesn’t look quite as technically impressive as other Showa Ultra works, it still was groundbreaking in its own right. Nothing on TV like Ultra Q had existed before this point. Nothing had showcased such a wide variety of creatures and advanced special effects in such a manner than ever before, and people ate it up. Radio shows, magazine articles, and even mangas would pop up due to this success. Everyone wanted a piece of that Ultra Q legacy and recognition.

I want to drive home the impressiveness of Ultra Q because I think it gets overlooked in the current Ultra-fandom environment that often focuses on newer shows. Because it’s a black-and-white program without a superhero character, first-time visitors to Ultra often pass over Ultra Q to get to the colorful various Ultramen incarnations and their superhero action. I rarely see anybody in online fan communities recommend Ultra Q as the best starter show for new viewers.

Well, I’ll make that recommendation, because Ultra Q creates the entire framework of what the franchise is. It’s a unique work of television science fiction and fantasy that needs to be better known to Western audiences. The episodes are by turns exciting, scary, weird, hilarious, and profound — and they looks fantastic, like a thirty-minute feature films delivered to your television set. I understand why audiences in 1966 went bonkers over it and so many recall it fondly today.

This was only the second Ultra show I watched in full, and my anticipation for it was high after years of reading about it. Tsuburaya and Co. did not let me down. This remains one of my favorites of the Ultra shows, and I’m glad that TsuPro has occasionally returned to its style with follow-ups like Ultra Q: Dark Fantasy and Neo Ultra Q. These shows remind viewers that the Ultra series doesn’t always need to have a superhero at its center. The imaginative storytelling and style of the franchise come from the vision of Ultra Q, which over its 28 episodes built a foundation for decades of great fantasy television. Tsuburaya achieved what he set out to do, what he always wanted to do: use special effects to create a world filled with both wonder and shadows, humor and horror, entertainment for children and adults.

If you’re reading about Ultra Q for the first time, give the show a shot and maybe follow along with my reviews. You can currently watch the entire show for free at several different streaming sites, and the Blu-set from Mill Creek is a bargain.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in the full story of Eiji Tsuburaya, seek out August Ragone’s 2007 book Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters — Defending the Earth With Ultraman and Godzilla, which is a major source I’m using for this site. You can also find extensive background on the show on Ultra Blog DX’s entry on Ultra Q’s production history and The Q-Files, an article originally published in Kaiju-Fan in 1996. I used these sources and several others when researching Ultra Q, such as Keith Aiken’s notes for the Ultra Q Blu-ray box set from Mill Creek.

Next: Defeat Gomess!